Pulling onto the tarmac of my grandparent’s driveway was always one of the best feelings in the world – especially in the summer. The air would always be hot and dry, and the lush trees and flowers my grandparents were so skilled at cultivating smelled so fragrant, nearly incapacitating the senses.

In the summertime, it was almost impossible to see their home from the unpaved street. Trees thick with peaches and nectarines concealed the humble two-bedroom dwelling my grandparents had raised 8 kids in. The flowerbeds with roses and tulips were also in full force, the damp soil beneath them probably flooded by the manguera. And if you looked hard enough to see beyond the abundant foliage, you’d still probably only see the bougainvillea flowers that draped alongside the house like thick braids of hair.

During the day, the driveway gate would be open – a metaphor for the kind of people they were. There would always be a couple of cars in the driveway from visitors – sometimes the cars of friends, sometimes the cars of their kids, and later, the cars of their grandchildren.

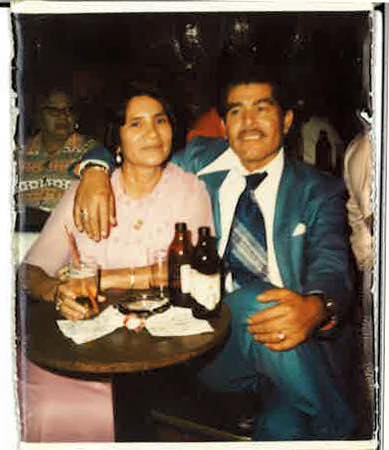

My grandparents were migrant farm workers, and they brought their green thumbs home every night to the land they purchased for $5000 in Fresno, California in 1967. My grandparents came to the United States from northern Mexico 10 years before that, following the crops from Florida to Washington state. They settled in California in the late 1950s, and had 8 kids over the course of 10 years. Despite being poor people for most of their lives, they were happy – because the most important thing to them was their family, and they had plenty of that.

As a kid, it always amazed me at how good they were with plants – not just the ones that helped to feed their family, but also flowers, succulents and shrubs that were all thick with insects and snails. As an adult, I’m amazed at how committed they were to it. Their occupation was literally back-breaking work, and when they weren’t out in the fields, they were corralling 8 children. Where they found the time, and the energy, to pull weeds and harvest was a mystery to me. But now I think I get it.

My grandparents loved plants. They loved ripe pieces of fruit – they loved presenting heavy, knotted plastic bags full of peaches and plums to their children to take home. They loved putting flowers in vases. I once caught my grandmother in her yard, manguera in hand, inhaling the scent of a rose deeply with her eyes closed. When she was done, she smiled at it, cupped it in her hand as if to give it a hug, and released it. She saw me and smiled; I smiled back.

The only thing they loved more than their plants was their family. My grandparents didn’t love picking grapes and strawberries in the hot sun from dawn until dusk – but that’s the price they paid to keep their family fed. They weren’t rich people, but the skill to harvest fruit was a gift. The fruit they grew was free, but all of us – my mom, my sister, my aunts and uncles, my cousins – have fond memories of eating pieces of fruit with my grandparents. They were gifts from them. And they loved us.

I’ll never forget the sacrifices they made so that I could have the opportunities I have, and become the man I am today. Although neither of them are with us anymore, their unwavering dedication to family, their superhuman work ethic, and their love for a cold, crunchy bite of watermelon in the summer lives in me. I am reminded of them every day.

I spent almost a month in Fresno last March while my grandmother lay dying in her bedroom. The garden hadn’t bloomed just yet, but one tree was producing so much grapefruit, I was squeezing them everyday for three weeks for fresh juice. My grandmother was in the other room, practically comatose, and couldn’t enjoy the juice, even though I know she would have. My grandfather had also been gone for over 20 years at that point, but I knew that the juice was one of their final gifts to me.

So I drank it in the yard and admired the garden’s buds, getting ready to bloom.